In the closing decades of the nineteenth century, the interfluvial plains of Punjab were in the midst of being transformed into a vast wheat and cotton commodity frontier. This period of British rule was marked by accelerated sociospatial and territorial restructuring as the colonial state sought to expand commodity production and incorporate regional agrarian economies into the global agrifood system through fixed capital investments in infrastructures of extraction, production, and circulation. In western Punjab, this took the form of a massive network of irrigation canals, “canal colonies,” and market towns that transformed parts of its sparsely settled, semi-arid plains into specialized subregions of commodity agriculture. This project traces the effects of commodity expansion in Punjab on the growth and development of Karachi. By 1910, the port of Karachi handled greater quantities of wheat than any other port in the British Empire. Nearly all of this wheat was produced in the canal-irrigated tracts of Punjab and transported to Karachi from where it was exported to Britain, Western Europe, and Japan. Through research in multiple archives in the United Kingdom, this project will examine (i) the development of interregional links between the wheat and cotton producing zones of Punjab and Karachi; (ii) the rapid expansion of the port and associated infrastructures during the late-nineteenth century; and (iii) the transformation of Karachi as a result of its integration into circuits of commodity export. This research forms part of a broader project that seeks to develop a world-ecological theorization and periodization of capitalist urbanization. It does so re-examining cycles of industrial urbanization in relation to historically specific formations of the global agrifood system, and associated processes of regional restructuring, since the late-nineteenth century.

Researcher: Swarnabh Ghosh

Swarnabh Ghosh, HMUI Grant Report, September 2022

I.

This research, which forms part of a larger dissertation project, traces the infrastructural underpinnings of the dramatic expansion of primary commodity production and circulation in Punjab in the late-19th and early-20th centuries—a conjuncture of intensified territorialization and accelerated sociospatial restructuring as the colonial state sought to expand commodity production for the world market through fixed capital investments in irrigation, transportation, and logistics infrastructures.1 In western Punjab, this took the form of a massive network of irrigation canals, “canal colonies,” and market towns that transformed parts of its sparsely settled, semi-arid plains into specialized subregions of commodity agriculture. I examine the sociospatial preconditions and consequences of commodity expansion by tracing the development and growth of the port of Karachi during the period of irrigation-led agrarian intensification.

II.

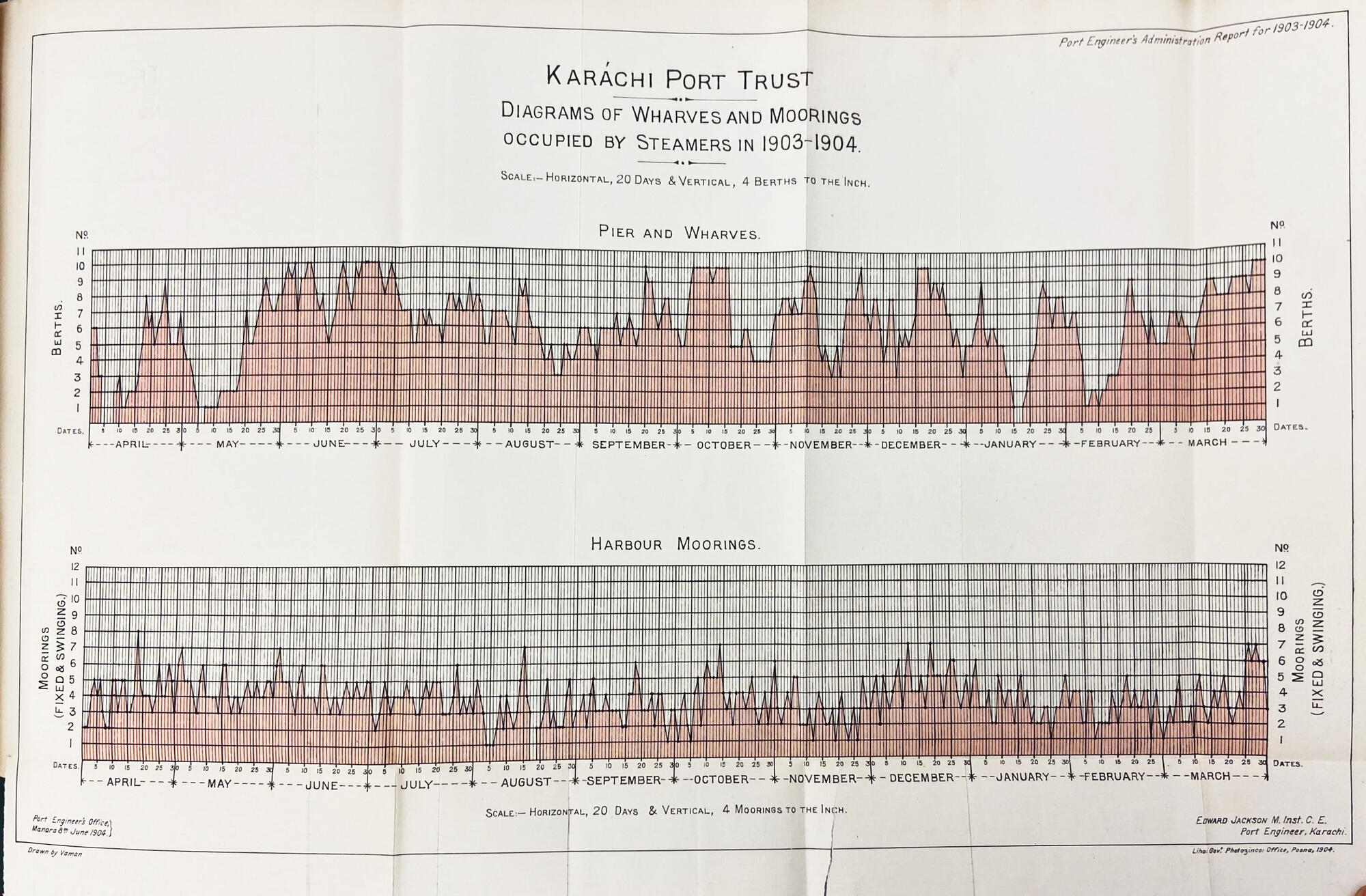

By the last decade of the 19th century, Karachi became a central node in the international export of commodities—principally wheat, cotton, and oilseeds—produced in the newly irrigated croplands of Punjab. By 1910, Karachi port handled larger quantities of wheat than any other port in the British Empire. The transformation of a minor regional port into a major node in international supply chains involved a range of processes including the establishment of the Karachi Port Trust, the construction of harbors, wharves, and dockyards, the installation of cranes and warehouses, and the establishment and continual maintenance of shipping channels through large-scale dredging.

In this regard, the commodity revolution in late-19th century Punjab rested upon a wide ranging infrastructural revolution that facilitated the production and circulation of export commodity crops alongside the integration of peasant households and subregional agrarian economies into transnational circuits of capital and an emergent global food regime. This infrastructural revolution, through which the late-colonial state sought to secure the “general conditions of production,” I argue, is key to understanding the uneven and combined trajectories of capitalist development, geographical change, and agroecological crisis in the region in the later 20th century.2

1 Manu Goswami, Producing India: From Colonial Economy to National Space (Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

2 Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (London ; New York: Penguin Books in association with New Left Review, 1993), 524–33; see also James O’Connor, “The Conditions of

Ghosh 1

The present project explores one dimension of this history by examining the geographies of commodity circulation in late-colonial India. It places the late 19th century project of commodity frontier expansion in Punjab within the broader, interregional matrix of sociospatial and socioecological relations that both enabled and constrained capitalist development in northwestern India.3 The construction of thousands of miles of irrigation canals through a coercive labor regime led to the partial overcoming of the vagaries of seasonality and secured a rapid increase in agricultural output. The expansion of irrigation enabled the production of wheat and cotton, which were transported by rail to Karachi. From here, they were loaded onto steam ships for export to United Kingdom, Western Europe, and Japan.

More than any other commodity, it was wheat that exerted a determining influence on the development and expansion of the Karachi port. In 1903-04, the quantity of wheat exported from Karachi exceeded one million tons for the first time leading a port official to make the following observation:

“There was a very marked increase in both the number and tonnage of steam ships making use of the Port, larger ships having been brought out chiefly to meet the requirements of the Export trade in grain.”4

In that year, 694 steam ships entered the port of Karachi. The next year, this number increased to 861 with the average tonnage of ships exceeding 1700 tons. The increase in exports and the concomitant rise in commercial maritime traffic exerted considerable pressures on the lagging infrastructural capacities of the port. An annual report noted that:

“The need for altering and extending existing arrangements in order to provide all the facilities which modern trade demands, has, for a long time past, been under the consideration of the Trustees and was emphatically forced upon their attention by the great increase of shipping […] during the wheat export season of 1904.”5

The export season of 1904 was soon surpassed by the export season of 1905-06, a record year for wheat exports. It was also a record year in another sense—the total quantity of

Production and the Production of Conditions,” in Natural Causes: Essays in Ecological Marxism (New York; London: Guilford Press, 1998), 144–57.

3 On “commodity frontiers” see Jason W. Moore, “Sugar and the Expansion of the Early Modern World Economy: Commodity Frontiers, Ecological Transformation, and Industrialization,” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 23, no. 3 (2000): 409–33; see also Sven Beckert, Ulbe Bosma, Mindi Schneider, and Eric Vanhaute. “Commodity Frontiers and the Transformation of the Global Countryside: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Global History 16, no. 3 (2021): 435–50.

4 Administration report of the Karachi Port Trust, 1903-04, India Office Records and Private Papers (IORPP), British Library, London UK, 5.

5 Administration report of the Karachi Port Trust, 1904-05, IORPP, British Library, London UK, 12.

Ghosh 2

material dredged around the harbor exceeded, for the first time in its history, one million tons.6

In response to signs of a looming crisis of capacity, the colonial government initiated a wide ranging “scheme of improvements” to meet the infrastructural demands of the export trade. Improvements included the extension of wharfage and the construction of new import and export yards. To undertake the first phase of this project, the Karachi Port Trust applied for sanction to raise Rs. 4.5 million. Additionally, a proposal was mooted to modify the legislative basis of the Karachi Port Trust—the Karachi Port Trust Act of 1886—to improve its borrowing powers “in view of the heavy expenditure necessitated by the already rapid increase of trade, import and export, which will be further augmented by the completion of the Punjab irrigation works […]”7

III.

The sketch outlined above encapsulates some of the findings of the research supported by the Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative. Through an examination of the records of the Karachi Port Trust and the Bombay Presidency as well as the papers of erstwhile “managing agencies” involved in the export of wheat and cotton housed at the British Library and the London Metropolitan Archives, I have attempted to trace the infrastructures of production and circulation that enabled the colonial state and commercial capitalists to forge new supply chains in a period of global geopolitical economic restructuring and intensifying inter-imperial rivalries.

____________________________

6 Administration report of the Karachi Port Trust, 1905-06, IORPP, British Library, London UK, 10. 7 Ibid., 12-13.