Instructor:

Course: Reconceptualizing the Urban: Berlin as Laboratory

Students: Hai-Li Kong

This project uses post-tourism demands and infrastructure to understand how Berlin’s city policies and marketing efforts are physically altering the urban environment. Despite Berlin’s financially weak status (close to €63.5 billion in debt), the city’s tourism sector has been strong. The number of annual overnight stays increased from 7 million in 1993 to 25 million as of 2012. As of 2011, over 275,000 Berliners were employed in the tourism business and the tourism industry boasted a gross turnover of €10 billion, thus contributing substantially to the city’s taxable revenues. Given how well the tourism sector has been faring, it has gained the attention and support of city officials.

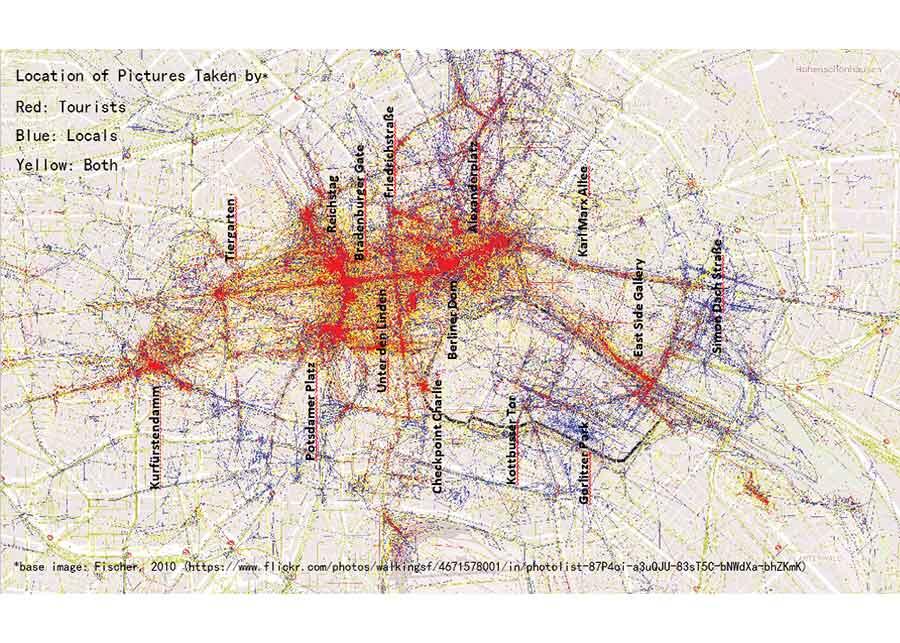

But it is important to note that Berlin is attracting a certain kind of tourism—what some researchers call post-tourism. In short, post-tourism blurs the line between work and travel. Post-tourists want personal experiences that ingrain themselves in the ‘every day’ and ‘authentic’ life of a neighborhood resident, such as visiting flea markets, appreciating local art, and exploring the underground music scene. This mapping project focuses on Luisenstadt in comparison to other Berlin neighborhoods. Luisenstadt is a former quarter of central Berlin and is now divided between present day Mitte and Kreuzberg, though it mostly encompasses Kreuzberg’s famous SO 36 area. This project focuses on Luisenstadt because the area seems to embody the demands of post-tourism. Between 1993 and 2011, overnight stays have increased from 148,000 to 2.8 million in south east Kreuzberg. Yet there are no major tourism-sanctioned attractions such as museums, monuments, or designated historical sites in Luisenstadt. Despite not boasting tourist-sanctioned sites, Luisenstadt sees a lot of post-tourists interested in the area’s burgeoning nightlife, street art scene, and alternative culture.

Starting in 2000, policy makers and marketing campaigners promoted alternative leisure sites and creative work spaces more in order to attract post-tourists. This project views alternative leisure sites as temporary use spaces that were formalized then advertised in tourism marketing campaigns. By the 2000s, policy-makers realized that unofficial activity happening in vacant urban spaces—once perceived of as a sign of failure—could be promoted as an attraction. Thus, certain squats became legalized housing projects, beach bars got long-term leases, and nightclubs got licenses. Creative work spaces mainly alludes to the burgeoning start-up scene which is backed by the city government. For example, Berlin has new initiatives that provide affordable workspaces, public subsidies for small organizations, and start-up centers in order to encourage entrepreneurs to found ‘creative spaces’ in hopes of getting the post-tourist to stay and set up shop.

While mapping out alternative leisure sites and creative work spaces may reflect where Berlin officials and marketers are focusing their efforts, understanding where post-tourists actually go may show how effective the city government’s efforts are. Because post-tourists characteristically stay for a few months, the locations of short-term rental spaces may reflect which areas attract more post-tourists than others. As opposed to hotels and hostels, short-term rentals allow for post-tourists to seamlessly embed themselves into the everyday life of a neighborhood. In Berlin, AirBnB is a popular platform used to access such short-term rental spaces

The presence of a short-term rental platforms like AirBnB can also have unintended consequences on urban fabric. Because post-tourists demand ‘authentic’ and ‘local’ experiences, they are interested in the same housing, retail, and entertainment infrastructure that city residents also prefer. But most post-tourists usually are willing to pay more than locals can afford. Therefore, rises in rents are frequently blamed on transient post-tourists who are neither residents nor conventional tourists and tourism has been blamed for causing or accelerating gentrification processes. As the physical presence of AirBnBs are easy to see, anti-gentrification sentiment can turn into anti-tourism sentiment as the popular ‘Berlin does not love you’ stickers that proliferated Berlin’s streets in 2011 exemplifies. However, while an important part of the conversation, it is important to note that tourism should not be solely targeted and vilified for causing gentrification. Even though it may be easier to point a finger at tourism’s tangible infrastructure, changing tourism infrastructures should rather be seen as symptomatic of how city politics and marketing agendas at large are intentionally or unintentionally allowing for the displacement of certain residents.