In 1748 a collection of Ottoman bureaucrats and hydrological engineers set out to map the sprawling system of aqueducts, collection basins, conduits, and fountains that sustained the residents of Istanbul. This was a period defined by repeated and severe shortages of water in the city. As the city's population soared in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, residents of Istanbul from multiple social classes labored to access this scarce resource, attaching private conduits to the city's waterway system, tapping existing conduits, and digging wells and ditches alongside leaky pipes. In numerous extant records, Istanbul's Havass-ı Refîa court, assigned to all water-related cases, endeavored to track and record these hydrological activities underway in the city, notarizing and legitimizing some while forbidding others and marking them for destruction. In studying these court records alongside the city's waterway maps, this project examines the legal and cartographic tools used by the Ottoman state to control Istanbul's water and the practices by which the city's residents acquiesced to and contested this control. In doing so,

"Mapping Water Shortage" explores both the material sites of urban politics in early modern history as well as methods in articulating the social production of environmental scarcity, more broadly.

Researcher: Nathaniel Moses

Project Documentation

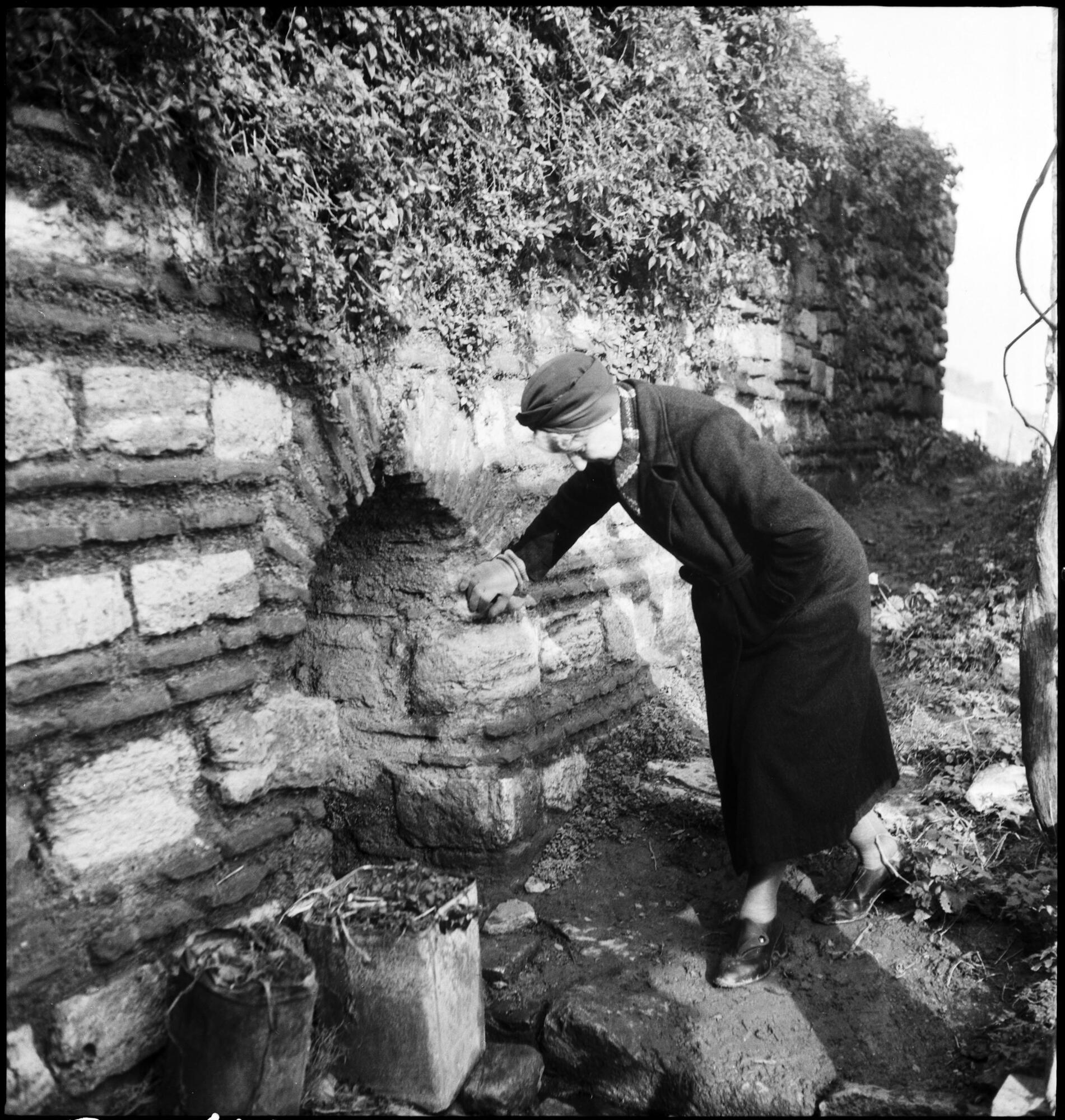

Figure 1. Woman standing next to a water conduit in the Samatya neighborhood of Istanbul in January 1944. Photograph by Nicholas V. Artamonoff, housed in the Dumbarton Oaks and Harvard University collection, “Nicholas V. Artamonoff photographs of Istanbul and Turkey, 1935-1945.” http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/8001390193/urn-3:DOAK.RESLIB:34328314/c...

My project this summer investigated the social history of water shortage and water theft in early modern Istanbul. Istanbul’s population expanded rapidly starting in the late sixteenth century and, along with it, so did demands on the city’s complex water distribution system. In this period most of Istanbul’s water was carried by extensive conduits to the city from rivers and wells in Istanbul’s northern and western hinterlands. As these conduits were tapped by an increasing number of city residents, water pressure dropped and state documents began to proliferate on the topic of water shortage (su killeti) and how to address it.

Over the course of the summer, using several Istanbul libraries and archives, I translated and interpreted a number of these documents. Whereas state responses to water shortage in Istanbul pertaining to the built environment—i.e. dam-building and well-digging ventures—have been studied at some length by architectural historians such as Kâzım Çeçen, I found that many state documents, especially imperial decrees, attest to a social struggle for water between imperial administrators, other elite actors, and a range of Istanbulites accessing water across the city and its peripheries. My reading of these documents was guided by the question, how did water—and efforts to use and control it—condition social and political life in early modern Istanbul?

One of the clearest conclusions to emerge was the repeated link between water theft and water shortage. Imperial decrees from the period repeatedly blamed those illegally using Istanbul’s water for the scarcity and sent out investigatory missions across the city to document and destroy the means of water theft. Here is the opening section of a 1608 decree on the topic of Istanbul’s water shortages:

In the well-protected domain of Istanbul, both within and outside the citadel, along the length of the Kırkçeşme and Kâğıdhane water channels, some people plant fruit trees on top of the channels, thereby stopping [the flow of water] within their houses and gardens. They also dig wells and privies. They are stealing the [city’s] waters and using them to water their fruit trees and vineyards. Water does not flow into Istanbul as it has been established. Since these [acts of theft] have caused the flow of water into Istanbul to reach the status of a shortage and of irregularity a waterway worker went to investigate the matter.1

I argue that this imperial narrative must be read critically alongside other social forces at play in Istanbul’s water history of this period. The historian Deniz Karakaş has recently demonstrated that, beginning in the early seventeenth century, an institution called the katma led to the partial privatization of Istanbul’s water supply.2 Katmalar, “additions,” were modest waterways funded by a private sponsor—often the house of a vizier or other elite official—and connected to the larger systems of sultanic water conduits in the north and west peripheries of the city. By adding a certain amount of water to the system, the katma’s sponsor was entitled to exclusive use of a portion of the added water, usually two thirds.3 Katma patrons frequently petitioned the state to protect their purchased water supply by addressing neighboring, illicit water usage.

1 This document can be found in Ahmed Refik, Hicri on Birinci Asırda İstanbul Hayatı, 1000-1100 (İstanbul: Devlet Matbaası, 1931), 50-51. The translation is mine.

2 See Deniz Karakaş, “Clay Pipes, Marble Surfaces: The Topographies of Water Supply in Late 17th-/Early 18th Century Ottoman Istanbul,” (PhD diss., Binghamton University, 2013).

3 Karakaş, “Water for the City” in A Companion to Early Modern Istanbul, ed. Shirine Hamadeh, Çiğdem Kafescioğlu (Boston: Brill, 2021), 321.

Elite and imperial anxieties regarding this process of propertization provide an important context for understanding the discursive deployment of “water shortage” and “water theft” as concepts within the imperial decrees. Both concepts worked to censure the ways in which many residents of the city accessed water—by planting trees above conduits, tapping cracks in pipes, digging wells in ways that leached water from neighbors or conduits, etc.—and apportion that water to residents in the city’s center, perhaps especially those new owners of water, the katma patrons. Within this discursive analysis, a third concept appeared repeatedly as a normative tool of state hydraulic power, “material greed” (tama‘-ı hâmları), leveraged as an accusation against the “water thieves” of the city.

The imperial decrees studied within the project shed light on the popular struggles that occurred across the city as state officials—the city’s Waterways Superintendent (su yolu nazırı) and his waterways workers (su yolcuları)—attempted to investigate and destroy illicit means of accessing water. For one, just as the imperial decrees leveraged accusations of theft and greed, in some instances it appears that those being accused of theft in turn accused the state investigators of stealing their means, as is reported in one of the decrees. Not only were these categories unstable discursive tools but they were tools wielded in multiple directions by state and non-state actors within the daily contestations of material, urban governance.

Alongside this conceptual terrain, the struggle for water was an arena in which state and subject articulated contesting claims to urban space in early modern Istanbul, particularly private space. The imperial decrees reflect an anxiety regarding the movement of water through hidden, unseen, and domestic spaces which evade state control. The water conduits themselves flowed

underground through much of the intramural city in the period, a significant problem for waterways workers attempting to observe and record breaches and cracks of various sorts. Houses and shops were built on top of municipal water pipes, hiding basement wells drawing illicitly from the city’s water. This built environment of Istanbul’s water meant that, to fight water shortage and water theft, state officials attempted to enter homes, observe, document their interiors, and potentially destroy crucial domestic infrastructure as a final result. Some residents turned away these investigators at their doors. One decree states that “when they [the waterways workers] attempt to observe the pipes, some of them [the offenders] [say] “I am a widow” and some of them [say] “my husband is not ready” by way of refusing the waterways workers entrance. Others, moreover, being of the janissary corps, prevent [the waterways workers from entering].4 As the hydraulic state came to assert itself in the surveillance of the domestic, we catch glimpses of popular politics not in new public spaces but rather in defense of the private, spaces where unsanctioned activity could proceed.

Thanks to the generous support of the Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative, this project allowed me to chart these conduits of urban social and political life in early modern Istanbul. For the unnamed water users investigated and surveilled as described in the documents, the struggle for water was a significant and underexamined context within which these individuals encountered state authority. The flow of water through the early modern metropolis, then, grounds and re-spatializes our conception of the city as a political and material entity; in this view, cracked water pipes and the trees planted above them, surreptitious basement wells, and doorway encounters between water users and waterways workers (su yolcuları) were critical sites for the making of state and popular claims to urban property and space.

4 BOA, MAD. d. 68, 41 (21 Rebiʿül-ahir 999/13 July 1591). Transcribed in Abdullah Martal, "XVI. Yüzyılda Osmanlı İmparatorluğunda Su-Yolculuk (20 Belge ile Birlikte)." Belleten (Türk Tarih Kurumu) 52, no. 205 (1988): p. 1647-1748.

Keywords: water, Istanbul, property, political ecology