Instructor:

Course: Reconceptualizing the Urban: Berlin as Laboratory

Students: Claudia Tomateo

The research asserts that informality can be pictured as a morally and legally questionable non-regulated matter but also as an urban or collective cultural asset. These interventions through the city are important in order to create a diverse and active atmosphere in contrast with the idealization of a modern city, but also as a process to create bridges between civil society and the government institutions with the objective to understand social dynamics from a bottom–up perspective.

The research focuses on analyzing the levels of informality in specific case studies in terms of the relationship between governance and citizen participation, taking into consideration the implications of rights and obligations to become a value proposition to the city. Furthermore, the objective is to understand the materialization of governmentality into physical locations and social structures that works in parallel with the mainstream of government regulation, but that certainly complements it.

Conclusions

Of the three cases presented, neither has a strong relationship with the municipality. The Municipality leases land or allows its use for agriculture, culture, and housing, among others. Other than that, the municipality does not subsidize any of the activities taking place there, even though they constitute an important input to the city. However, in each of the three cases presented the relationship is slightly different.

In the case of Prinzessinengarten the lease is temporal; this means that the Municipality is not interested in securing this activity because they may have more profitable plans.

In the case of Holzmarkt they are in negotiations to actually sell the land, but in this case many other institutions and sponsors exert pressure with a specific plan for the area. Holzmarkt remains regulated by the municipality’s policies.

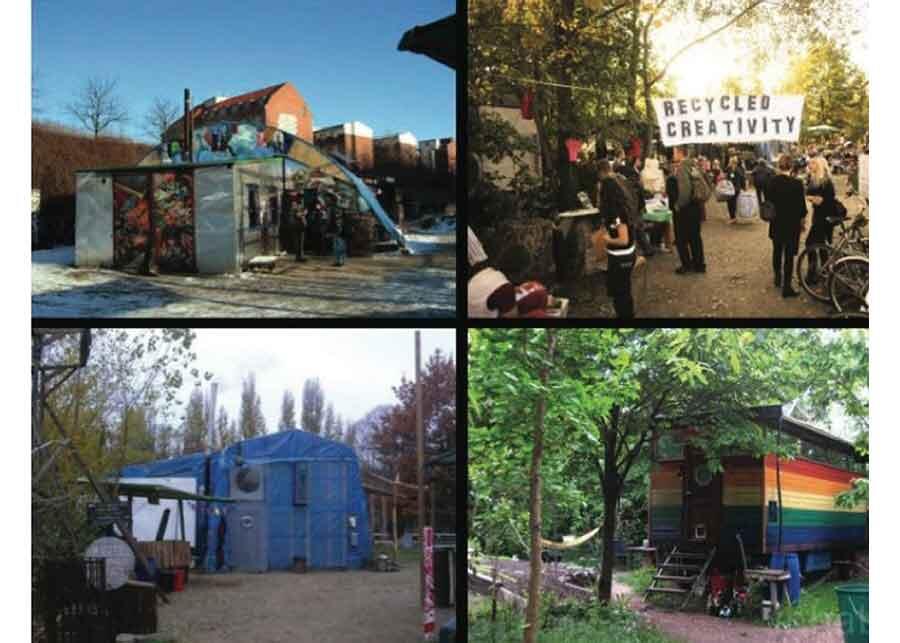

In the case of Lohmüle the municipality tolerates the illegality of land appropriation (the users do not officially own the rights to the land) because of the good contribution the users make to the community, including their cultural agenda. Moreover the users maintain good relationships with the neighbors and the media.

The decision of the government to keep a certain distance from the alternative settlements gives space for ideas of community and active citizenship to act as strategies enabling the state to govern more effectively, allowing for diverse and improved life for the citizenry. Even tough certain informal settlements establish their own rules and subscribe to ideologies different from the municipality ideals, this strategy to manage the informal settlements from the outside from the municipality owning the land is a political strategy to actually manipulate certain events and decisions without being spotted. For sure, there are different levels at which this is manifest, Holzmarkt is the one that is more politically regulated, in that it is used to build the image of a “creative city” in a superficial way, not necessarily embracing creativity and culture as a tool to make an argument about the contemporary issues that the city is facing. In this case the cultural agenda is used to simulate the “creative city” image that attracts tourists.

In the case of Lohmühle , the insertion of a cultural agenda is a key point for allowing the project’s permanence over time. It is not only a way to promote themselves and have a better relationship with the neighborhood and media, it is also a way to justify the use of the land and keep living there – it is a job.

There are some dangers when policies about informal settlements are not imagined as a means of getting closer to the community and of enabling diversity in the neighborhood. There is the danger of gentrification when the “creative city” motto becomes a pervasive trend and the “edgy” aura of the community in question actually attracts new types of neighbors. The municipality should do their best to prevent the processes of gentrification in these areas, because it can put an end to the diversity and the dynamism of informality.

Cooperatives, trailer camps, and temporary projects within the inner city have an important role to play, especially in Berlin – a city characterized by its polycentric arrangement and empty spaces. The complexity, on one hand, of the equilibrium between what the city has provided to the community and what the community has given back to the city, and on the other hand, the distribution of power between the communities and the government institutions is something that has to be addressed and reflected on – by the representatives of the communities as well as the municipality.

As citizens we should embrace these interventions in the “formal” city because they give visibility to diversity, challenge decision-making processes and contribute to a productive conversation and thinking about the city. They play an important part in Berlin’s processes of transitional urban development.