Instructor:

Course:

Students:

Since its opening in 2003, Dong Xuan Center in a previous industrial zone in Lichtenberg has become a fairly well-developed spot for the provision of wholesale goods, gathering of Vietnamese community, and cultural exchange. This project studies the formation and operation of the market in a post-socialist environment in Berlin, and tries to analyze the different visions for its future by local Germans and the Vietnamese community.

Vietnamese immigration is not a phenomenon exclusive to Germany, but has been running in parallel with other eastern European countries, and past immigration is intimately related to the current condition. The project takes a look at different waves of Vietnamese immigration. They correspond with the timeline of modern Vietnam itself: the first wave –the student exchange program initiated among communist states in 1950s and 1960s; the second wave — the “boat people” — comprises refugees from South Vietnam emigrating to the Western Bloc after the country was taken over by the communist leadership; the third wave — the “contract workers” from Vietnam to COMECON countries as labor force for industrial production; and the later fourth wave — the “business immigration”, with Vietnamese people looking to fill economic niches in eastern Europe through their transnational relations after the collapse of the USSR.

In the case of Berlin, Vietnamese immigrants living in West Berlin are mainly “boat people” from the South Vietnam. They received language education and help to integrate themselves into the society, including assistance with seeking a job as well as housing. The Vietnamese living in East Berlin, along with people from North Korea, Mozambique, Angola, Cuba, and other Eastern Bloc countries, are mainly “contract workers” who arrived here in the 1980s when there was a shortage of cheap labor force, as well as immigrants who have been arriving since 1990s, using their family connections to do small business here. Struggling with integration, survival, and reputation, the earlier contract workers and the later economic immigrants have to rely on themselves for employment in today’s Berlin, thus they compose the main driving force behind the Dong Xuan market.

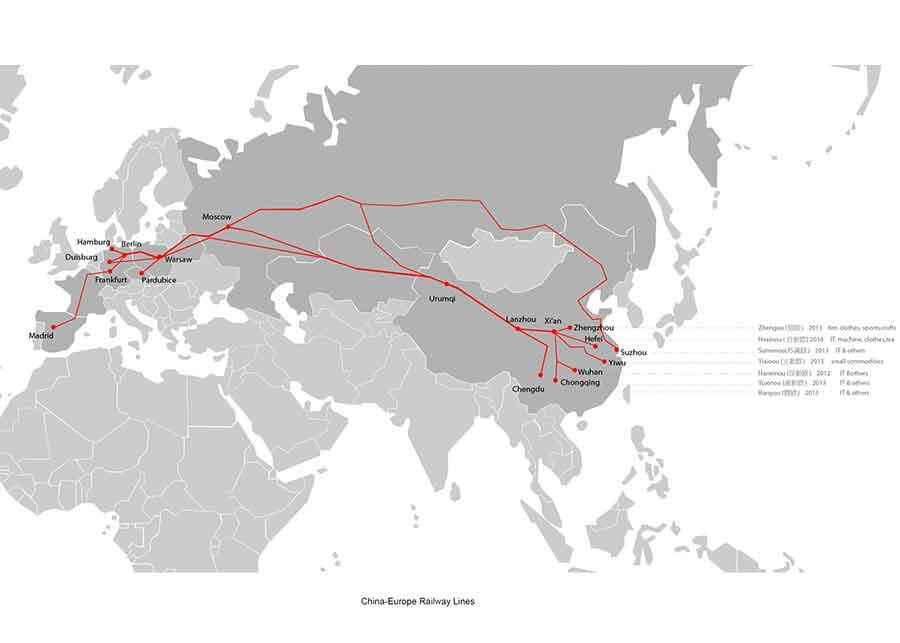

The operation of Dong Xuan Center relies on informal capital start-ups, kinship management, and updated trading routes. The mapping of transnational ties established by the Vietnamese during the socialist era reveals an otherwise invisible network among the Vietnamese who live in eastern Europe. Similar Vietnamese markets are established there, which make the circulation of goods, capital and information possible. The mapping of historical and contemporary trading routes for imported and exported goods shows the updated ways of obtaining cheap goods from China and Vietnam which secure a competitive price in the destination market, enabling the merchants to make a profit.

As to the future of the site, local German investors/developers have crafted a competing narrative of a potential art-related venue here in the future, which would contribute to the gentrification of the area, while the Vietnamese are trying to secure their “enclave”, expand their properties, and work towards a better and more comprehensive development of the site.